Video by Sierra Dotson

Democracy can fall quickly, so pay acute attention to government affairs, journalist Sevgi Akarcesme told faculty, staff and students during the “Death of Media Freedom” lecture on Wednesday, Feb. 12 in Grace Hall.

“The government regime took away my job, my career and… my family,” Akarcesme said, in regards to fleeing her homeland.

Akarcesme shared her first-hand experience of the fall of democracy in her home county, Turkey. Up until March 2016, she was the editor-in-chief of Today’s Zaman, one of the largest independent Turkish newspapers. On March 4, 2016, the paper was overtaken by the government, who wanted to censor the news. Two days later, she fled Turkey for Brussels, Belgium, to safety.

Akarcesme noted that 10 years ago she would have never imagined for these events to unfold.

“A decade ago, even myself, I could not have imagined Turkey becoming a dictatorship. I never thought I would have turned into a political asylum seeker in Europe.”

For decades, Turkey was a multi-party democratic country with dreams to join the European Union. However, the country has been heavily polarized in recent years.

In 2003, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, then mayor of Istanbul, was elected prime minister of Turkey.

Initially, Erdogan was well received and liked by many Turks for his inclusive political philosophy. He sought “civil rights” for everyone regardless of religious beliefs or ethnicity. Turkey also saw significant economic growth under his leadership.

His popularity persisted and went on to win subsequent elections. However, by 2013, Erdogan’s power began to take on an autocratic nature. In 2014, he was elected the President with a new constitution granting him increased authority after a nation-wide referendum.

According to Akarcesme, 2013 marked the “beginning of the end” for Turkish democracy.

During the summer of 2013, the government sought to demolish Gezi Park, a popular park in the heart of Istanbul. Locals gathered to peacefully protest. However, the government responded by using violence, such as tear gas or beatings, to dispell the crowd.

“Turkey witnessed the first and most important series of street revolts…Seemly it was a protest of a demolition of a park” Akarcesme said, referring to the Gezi Park protest. “But of course there were frustrations with Erdogan’s increasing oppression.”

By December, corruption charges unfolded against prominent figures in then-Prime Minister Erdogan’s cabinet. They were under investigation for receiving bribes from an Iranian-Turkish businessman, Reza Zarrab.

The situation became complicated after Erdogan placed the blame for the investigation on the Gulen Movement whom he later declared to be a terrorist organization.

“He declared the investigations as a coup attempt against him,” Akarcemse said.

According to BBC, the Gulen Movement, founded by Fethullah Gulen, “promotes a tolerant Islam which emphasizes altruism, modesty, hard work and education.” The global network also focuses on interfaith and cultural dialogue.

To hold on to power, Erdogan tightened the reigns on the country.

“The first target is always the media,” Akarcemse said.

Zaman Media Group, the parent company of Today’s Zaman, was persistent in covering the corruption scandal. This decision put them in a perilous situation.

After midnight on Dec. 14, 2014, police raided Today’s Zaman and detained the then editor-in-chief Ekrem Dumanli. Akarcesme, who at the time was a reporter, noted that he was released a week later.

Just over a year later, Akarcesme’s life was about to take a drastic turn.

“March 4, 2016, I think it marked the end of my life as I knew it,” she said.

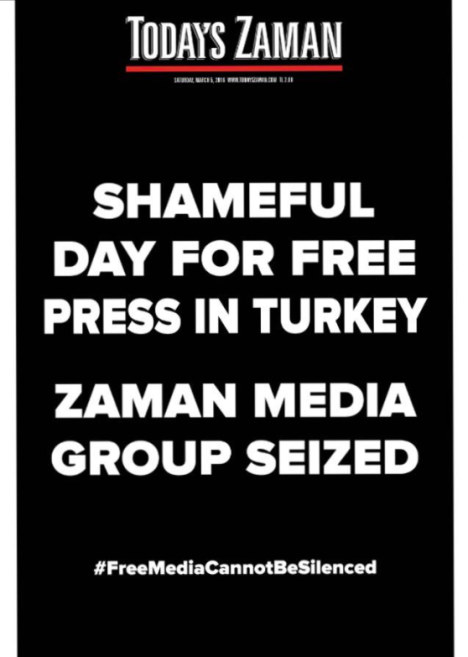

At 3:00 p.m. on Friday, March 4, 2016, editor-in-chief Akarcesme and her staff published their final uncensored issue of Today’s Zaman.

The front cover was completely black with the words, “SHAMEFUL DAY FOR FREE PRESS IN TURKEY ZAMAN MEDIA GROUP SEIZED” in white text.

Shortly afterward, the government raided the paper with the intention to seize it.

“There were counter-terrorism forces outside the building. They literally broke into the building…” Akarcesme said. “ They forced us to go out of the building. They almost detained some of us.”

Meanwhile, a large contingent of loyal Today’s Zaman readers peacefully protested peacefully outside of the office. Police responded by firing tear gas at them.

Within days, Today’s Zaman’s digital archives were deleted and the government implemented a staff of their choosing.

“In a way, they are rewriting history,” Akarcesme said, “according to their liking.”

Just two days later, March 6, 2016, Akarcesme packed her bags and flew to Brussels, Belgium. She is fortunate to have escaped the country, as most of her colleagues are currently in jail, hiding or have been exiled.

“[Turkey]is the largest prison for journalists at the moment,” Akarcesme said.

As for the present state of Turkish media outlets, Akarcesme notes that “not a single independent media channel exists.” The entirety of the Turkish press is under Erdogan’s power. The government crackdown is not limited to media entities. Erdogan also eliminated all those with ties to the corruption investigation.

According to Akarcesme, this resulted in the removal of “tens of thousands of judiciary members, judges, prosecutors and also security forces, police officers who were part of the corruption investigations.” Later, they were arrested and put in jail.

Anyone associated with the Gulen movement was at risk of being arrested. For example, if you were a teacher at a Gulen supporting company, you could be arrested despite having a clean record.

These arrests did not become widespread until the “so-called coup attempt” in July 2016.

On July 15, 2016, the streets of Istanbul were held captive by tanks and the Turkish military personnel entered into the streets of Istanbul. Nearby, Turkish jets bombed the Parliament.

However, Turkish residents were quick to respond to the event. Through the use of social media, they gathered in the streets, protesting and climbing on tanks, before distinguishing the coup.

However, this success came at a cost. 249 people were killed.

In the months following the coup, Akarcesme said that media companies and educational institutions were shut down.

She explained that the attempt was part of Erdogan’s plan.

“Erdogan knew that it was actually coming… it was a perfect pretext for him to complete his massive purge.”

Erdogan was so serious about purging the country of critics that he liberated 34,000 criminals to make room in the prisons.

Even though it’s been three years since the July 2016 coup, the future looks bleak for the imprisoned.

“You don’t have the right to see your lawyer after a certain point…most of these journalists or critics who have been jailed actually are not convicted,” Akarcesme said. “They are pending trial.”

Akarcesme also noted there are approximately 17,000 women and more than 800 babies are currently imprisoned.

The “so-called coup attempt” was eye-opening for Akarcesme, who gained an appreciation for the life she had in Turkey.

“Up until that time I took so many things for granted. I took my passport for granted, my rights, my constitutional rights for granted… I was a bureaucrat, I was a journalist, I had no problem traveling,” Akarcesme said.

For example, after moving to Brussels, Akarcesme had planned a trip to the United States. Just as Akarcesme was about to board the plane, her passport was revoked. According to the Turkish government, she was seen to be a terroristic threat. Fortunately, her passport, along with 50,000 others, was reinstated by the Interpol.

“[They] realized that this is a fake attempt of the government to silence and punish dissonances and critics,” she said.

In 2017, legislation was passed that would remove the prime minister position, increasing President Erdogan’s power and permit him to remain in office until 2029. Akarcesme sees Erdogan as a “dictator,” rather than a president.

She now resides in the United States. However, the thought of returning to Turkey is more of a dream than a reality.

“They would detain me right away on the plane,” Akarcesme said.

In closing, Akarcesme noted the importance of speaking up and holding others accountable to prevent the fall of democracy.

“We have to be vigilant and pay attention and raise awareness…” she said. “Because dictatorship is contagious.”