Editor’s note: Some names have been omitted to protect certain sources’ privacy.

Boiling to Death

“There’s an expression about a frog that defines my experience really well,” Leslie B. said. “If you put a frog in boiling water, it will jump out to save itself, but if you put a frog in room temperature water and slowly turn up the heat, it will boil to death.”

Leslie was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa when she was 15 years old.

“I was boiling to death and I had no idea,” Leslie said.

The National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA) defines anorexia nervosa as a serious and potentially life-threatening eating disorder that is characterized by self-starvation and excessive weight loss.

Warning signs and symptoms include intense fear of weight gain, dramatic weight loss and excessive exercise.

Although she was at her worst point when she was diagnosed at 15, Leslie said everything began a year or so prior, when she was 14 years old.

“At first, I would skip breakfast because ‘it nauseated me’,” Leslie said. “Then, I stopped eating lunch in the cafeteria at school because ‘nothing appealed to me that day’ and it got to the point where I’d have four bites of dinner before smushing everything around on my plate and throwing it away.”

Looking back now, Leslie realizes that her most severe point was about four months before she began treatment.

“I weighed in at about 100 pounds even,” Leslie said. “By the time I got to therapy I had gained one pound and I thought it was the end of the world.”

Leslie went to an inpatient clinic the summer she turned 16. She stayed in inpatient care for about a week and continued outpatient therapy for the subsequent four, where she met with a doctor three times a week.

According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, only one in 10 men and women with eating disorders receive treatment. Only 35 percent of people that do actually receive treatment get it at a specialized facility for eating disorders.

“I don’t know if I really understood what I was doing to myself until after I’d finished therapy,” Leslie said. “I’ve been in recovery since then, but I don’t consider my anorexia to have ever ended because I still deal with it to this day.”

With the highest mortality rate of any mental illness, eating disorders can be deadly if left untreated.

“I still struggle with the nagging voice in my head on particularly bad days,” Leslie said. “I’m stronger now, though, and I’m much better at ignoring it.”

Looking back, Leslie is proud of herself for how far she has come.

“I know my experience has made me who I am today, but it wasn’t my anorexia that made me stronger. I did that for myself,” Leslie said. “I picked myself up because nobody else did and I pushed myself forward to recovery because nobody else did.”

Most importantly, Leslie hopes to raise awareness for eating disorders and other people who may have similar stories.

“I want people to understand that no one starves themselves or throws up after every meal just for fun or for attention or for their spring break body,” Leslie said. “It’s an illness.”

“Skinny,” blonde and perfect

The NEDA found that girls especially will start to express concerns about their body around the age of 6.

Additionally, 40-60 percent of girls will become concerned about their weight and develop a fear of becoming “fat” in elementary school.

What does “fat” mean to a 6-year-old girl? How could a child so young be able to look in the mirror and say “I am fat.”

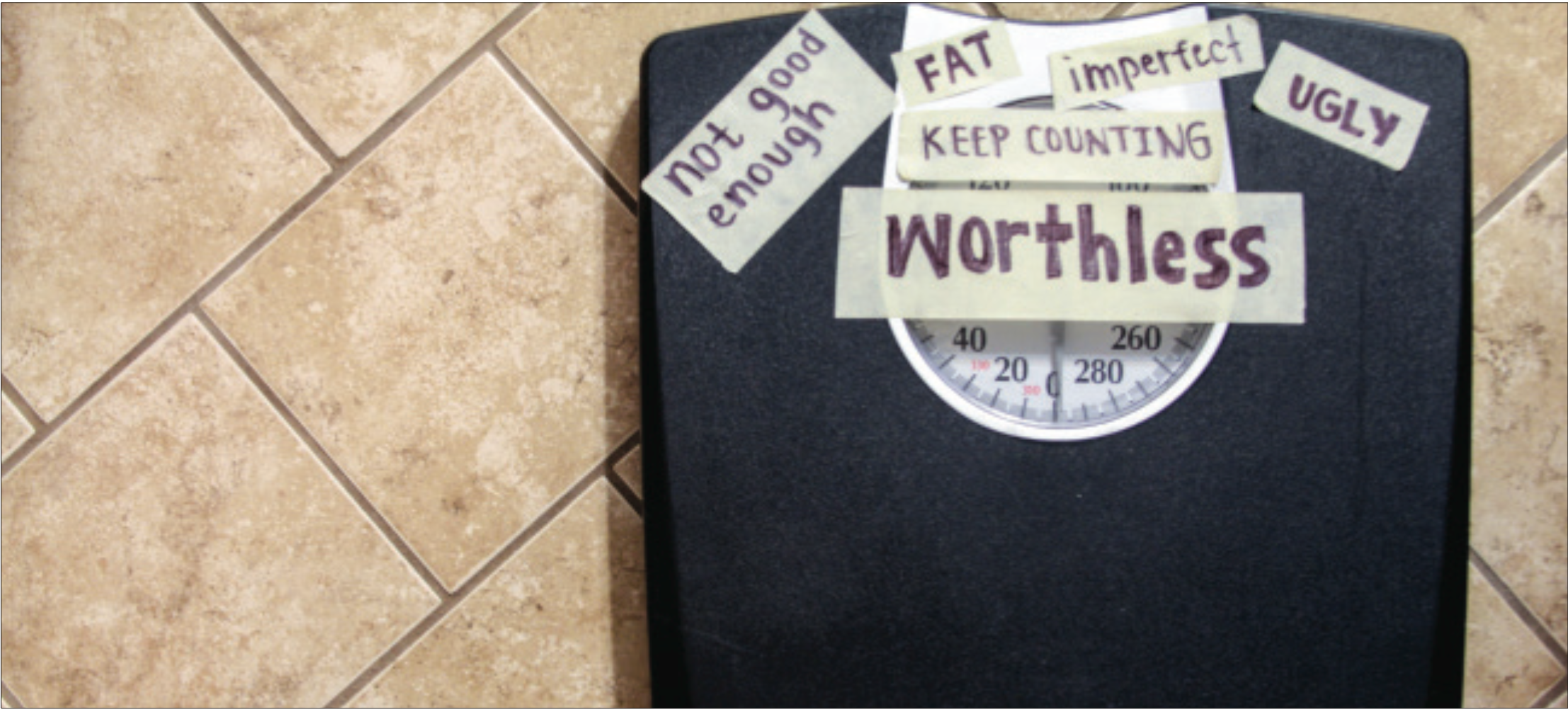

This idea of “fat” comes from negative body image.

Psychology Today defines body image as the mental representation one creates, regardless of how closely related it is to how others see you.

“You could be the ripest, juiciest peach in the world,” Tia Iezzi said. “But there is still going to be somebody who hates peaches.”

Iezzi is a 2015 graduate of Temple University. Her four-year battle with anorexia and bulimia began when she was 16 years old.

Looking back now, Iezzi realizes that the battle began long before her 16th year.

“I know my disorder came from a constant self esteem battle,” Iezzi said. “Ever since I can remember I was short and chubby.”

Self esteem and body image are closely related risk factors when it comes to the development of an eating disorder.

Men and women who suffer from self-esteem and body image issues will often compare their own body to others.

“I remember being at the store with my mom when I was very little,” Iezzi said. “I looked at a little girl around the same age as me and thought, “Why do I not look like her?” She was “skinny,” blonde and perfect and there I was short and chubby with dark unruly hair.”

Looking back, Iezzi recognizes that she was always uncomfortable in her own skin.

“I was always wearing baggy clothes and my hair was always pulled back in a bun,” Iezzi said. “It still saddens me that I spent so much time being upset about how I looked.”

Iezzi’s battle began when she got very sick at the beginning of her junior year of high school. After not being able to eat anything besides popsicles and pudding for a few weeks, she quickly noticed how much weight she had been losing.

“It was easy because all I was doing was sleeping and eating 200 calories a day,” Iezzi said. “I noticed how much weight I was losing and over the next six months, I gradually became obsessed with what, or lack there of, I was eating.”

Iezzi began checking the nutrition facts on everything she was putting in her body.

“If it had even a gram of fat in it, I wouldn’t touch it,” Iezzi said. “At one point I would eat an apple every morning for breakfast, wouldn’t bring a lunch to school and then would eat carrots when I got home. I would sleep for hours to curb the hunger and then wake up and eat a piece of bread or some rice for dinner.”

Iezzi got to a point where some days she would not eat anything except fruit. This starvation and restriction pattern went over for about year. She dropped 20 pounds.

Throughout her senior year, she slowly became more comfortable with eating, but still remained cautious. When it was time to head off to Temple for her freshman year, she was unwilling and less than happy about being in a new and unfamiliar place. Food became a source of comfort for her. She used it is as a security blanket.

“I was staying in on the weekends and eating pizza and fries to comfort myself,” Iezzi said. “I had an awful roommate, I didn’t care to make friends and I was dating a guy just so I wasn’t lonely.”

Spending her entire freshman year like that, Iezzi developed a binge eating disorder and gained another 20 pounds.

When she came home from school for the summer, she knew something needed to change.

“I started running and eating like a healthy person and I lost about 15 “healthy” pounds over the course of that summer,” Iezzi said. “I went back to school for sophomore year and this then turned back into anorexia, however not as severe.”

Iezzi found herself again checking nutrition labels and not eating anything unless she considered it “healthy.” When her weight didn’t change, she became angry with herself.

Iezzi never went into treatment because she was in such denial that she was actually struggling. However, some life changes in the last year or so have proven to be more than enough to help her turn it around.

“Junior year I found a nannying job that I loved and taught me that life was about so much more than just how we look,” Iezzi said. “I also mustered up the courage to end my incredibly unhealthy relationship and was single for a whole year for the first time since my ED began.”

Iezzi got an internship in which she had a lot of responsibilities. She also met someone and got into her first very healthy relationship.

“I finally felt like things were looking up and I suddenly had better things to worry about than the number on the scale,” Iezzi said. “It’s been a full year now and I haven’t looked back since.”

Dancing around it

Many parents, siblings and friends often do not know how to cope when someone they love is struggling with an eating disorder. It can be confusing and family members and friends may often feel very guilty or fearful that their loved one may not recover.

Regardless of the severity, eating disorders affect so many more people than just the person suffering.

Nicole Kline, junior psychology major at Cabrini College, has watched her younger sister battle anorexia and bulimia for three years now.

“Before she got sick, I never would have imagined the effect it would have on a family,” Kline said. “We slowly started to fall apart as she got more and more sick.”

The first person to notice something was wrong was Kline’s mother. She first observed her youngest child exercising excessively and pushing her dinner around on her plate, avoiding having to eat it.

“When it first started, everyone in my family was constantly arguing and trying to handle the situation in different ways,” Kline said. “We quickly realized that didn’t work.”

Recognizing that her sister’s disorder has changed her family’s dynamic, Kline worries they may be in a place that they cannot get out of.

“We put on a really good act most of the time,” Kline said. “We dance around it like everything is okay, while constantly worrying about what could happen next.”

Coming from a family that loves exercise, fitness and healthy eating, Kline says both she and her parents often forget that those topics might bother or trigger something in her sister.

“It’s extremely hard to be around her sometimes just because we do have to walk on egg shells when she is there,” Kline said. “Saying anything about that kind of stuff could set her off.”

Looking at her own relationship with her only sibling, Kline knows that she is the “target” for when her sister needs someone to yell at or to blame the situation on.

“She’s currently in a pretty bad place,” Kline said. “If anything, her disorder has made us less close.”

Recognizing that there are both good and bad days, Kline is currently working on trying to remain positive.

“Bad days can so easily break you down,” Kline said. “However, I don’t ever plan to stop trying to help her so that we can get back to where our relationship once was.”