Editor’s Note: The vast majority of domestic abuse survivors are women and the majority of abusers are men. As a result, throughout much of the research done on domestic violence, the perpetrator is often identified as male while the survivor or victim is identified as female. Many speakers during the symposium referred to perpetrator’s as “he” and survivors as “she.” For consistency, in this article, Loquitur will follow the same general rule; however, it is acknowledged that in domestic violence, anyone can be a victim, regardless of sex, gender, race, sexual orientation, class or any other classification.

When Nicole Peppelman began to understand she was trapped in an abusive marriage and recognized she would not be able to escape it on her own, she sought the help of her family, her loved ones and domestic abuse professionals.

Peppelman did everything she could to survive and protect those that she cared about. She contacted police when it got dangerous, she sought out refuge in the home of her older sister, she solicited the counsel of professionals and she went through the lengthy divorce process. She should have been a domestic abuse survivor.

Despite doing everything right, Peppelman died at the hands of her abusive ex-husband.

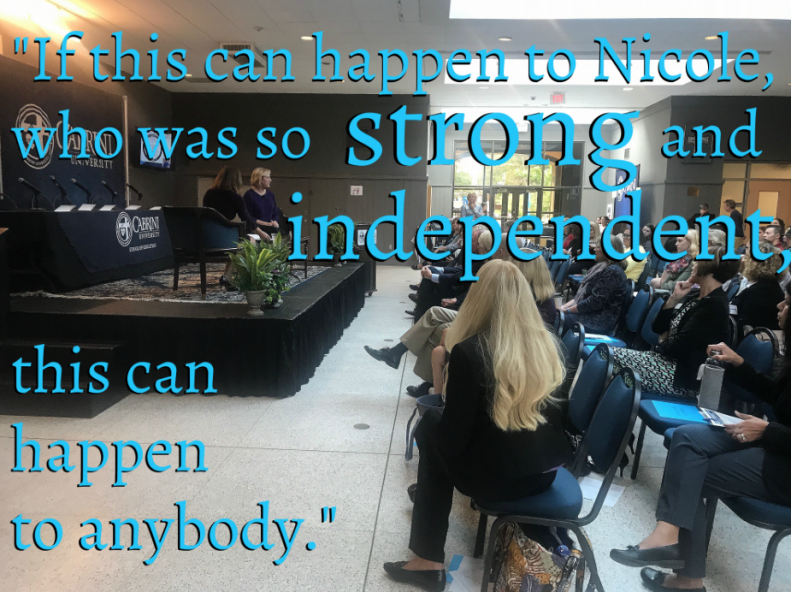

“If this can happen to Nicole, who was so strong and independent, this can happen to anybody,” Peppelman’s older sister Janine Rajauski said to the audience at Cabrini’s seventh annual Domestic Violence symposium.

Nicole Peppelman, similar to many women in an abusive relationship, found it difficult to leave.

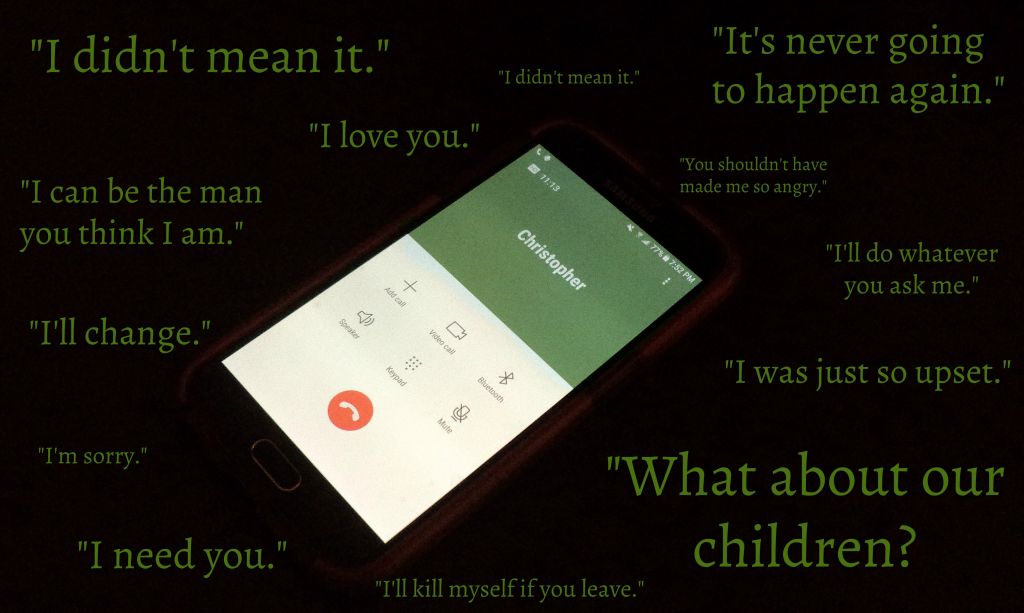

“It’s so frustrating; it’s so backdoored,” Rajauski said during the symposium. “He [the abusive husband] would go off the deep end. She would come to our house. Everybody would be okay for a few days. And then, he would start the calling.”

Nicole Peppelman would return to her husband because she wanted to make the relationship work for the sake of her three children. Peppelman also wanted to resolve the issues with her husband because she still loved him, despite the abuse.

“It’s just a really complex, horrible situation that’s really hard to get out of,” Rajauski said. “And in the middle of it is the person that married that person and who loves them.”

Peppelman and her husband got into the routine of him hurting her just enough for her to leave, him promising to change and her going right back to her abuser.

While many wonder why people stay in abusive situations, the message to the audience at the symposium was that people do it because they love their abuser and because they want to protect their family.

People stay in abusive relationships for a variety of reasons. They may be financially dependent on the other person. They may be trying to protect their children. They may be afraid of what will happen if they try to leave. A lot of times, it’s a combination of many of these things.

Peppelman mustered up the courage to leave her abuser at least five times.

On average, it takes survivors of domestic violence seven attempts before they permanently leave, according to the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

In the symposium, Rajauski said, “We shouldn’t be asking ‘why was she there that day’ or ‘why didn’t she leave?’ We should be asking: ‘Why is he abusing her?'”

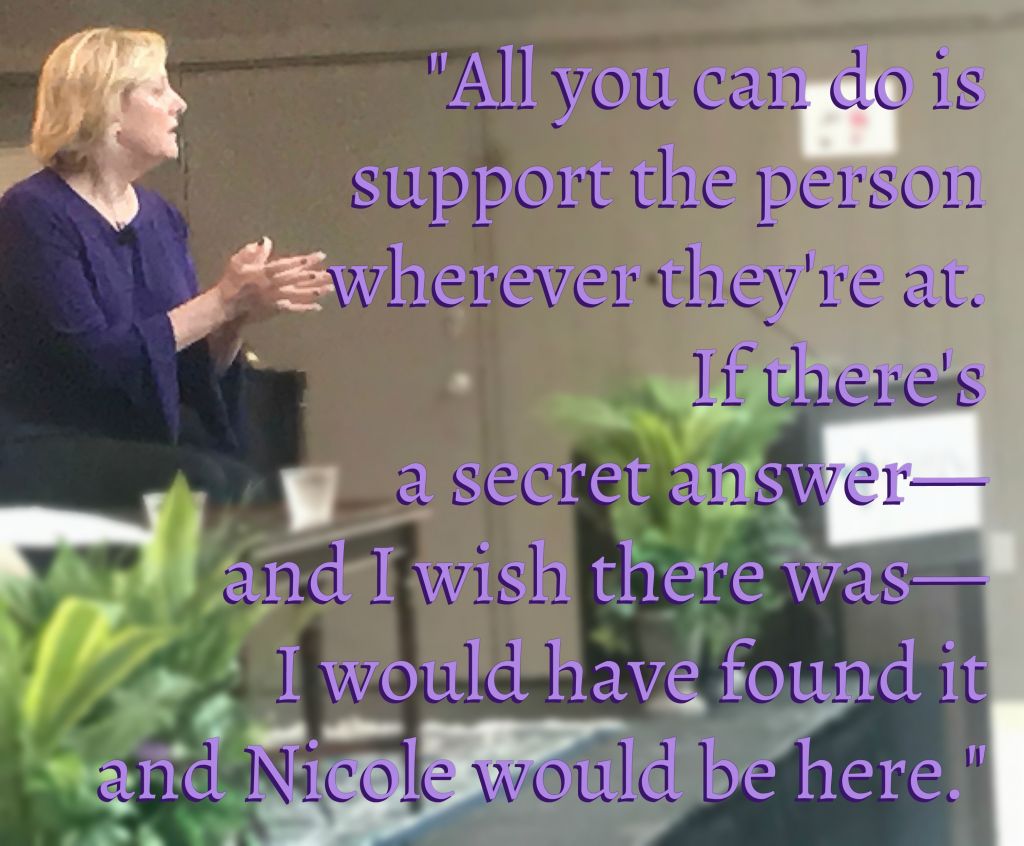

Unable to escape the cycle of an abusive relationship, it is important for survivors to have friends and family who support them.

Cabrini has a federal grant to educate about violence against women. Tommie Wilkins is the grant coordinator.

Wilkins said, “If you think a friend is in an abusive relationship, check in. Let them know you’re concerned about them. You can’t make anybody do anything, so it’s basically saying to them, ‘I’m worried about you. I’m concerned about you. If you need to talk, I’m here.’ And just kind of respecting their boundaries, because here’s the thing: you can’t step in and save them.”

Colleen Lelli, associate educational specialists professor and director of the Center on Childhood Trauma and Domestic Violence Education, said during the symposium that it is important for domestic violence victims to seek help before trying to leave a toxic relationship on their own.

“There are safe ways to leave,” Lelli said to the audience. “Please seek counseling first before you do that, because it’s really important that you understand how to do that safely.”

Domestic violence advocates acknowledge that education is the solution to this epidemic.

Husband and wife John and Barbara Jordan are domestic violence education advocates who have worked together on the issue of domestic violence for more than 20 years, along with multiple other community service projects.

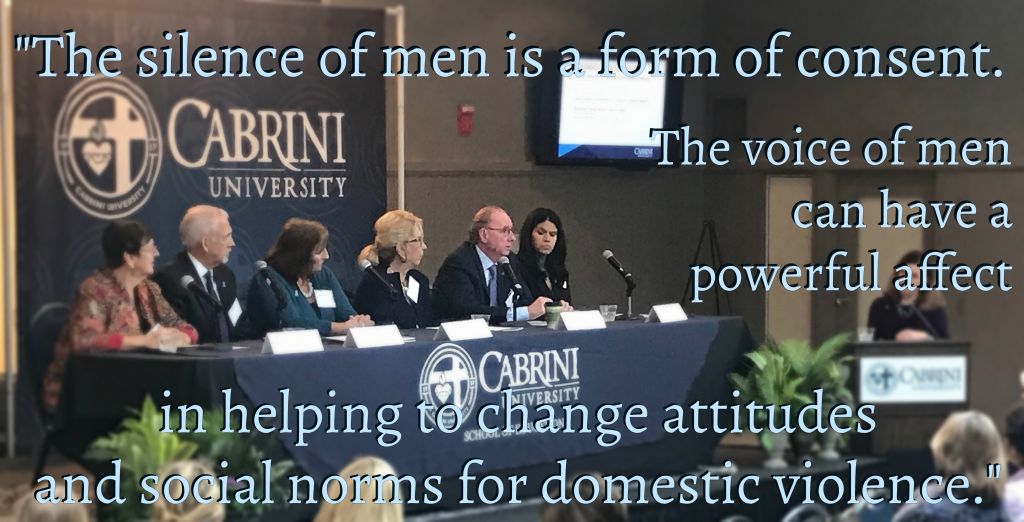

During the symposium, John Jordan emphasized that men need to become more engaged in the discussion of domestic violence.

John Jordan said to the audience, “Men need to accept that violence against women and children is not a woman’s issue. This is a man’s issue. Men are responsible for 99 percent of all rapes and 95 percent of all domestic violences are perpetrated by men. For any men that believe domestic violence is a woman’s issue only, I always say four words. I want them to remember: mothers, sisters, daughters and granddaughters. That relates to you, men.”

By excluding themselves from the discussion of domestic violence, John Jordan said that men are providing a form of consent.

Teaching men not to abuse and encouraging them to be not bystanders but up standers is part of the solution to domestic abuse. Additionally, educating the youth on domestic violence is also essential.

Janine Rajauski said, “I think the answer’s going to be teaching the children— teaching the middle-schoolers what abuse is and what it looks like. The problem is this younger generation doesn’t think it’s abuse; they think it’s romantic. So I think we’re going to need men to stand with us, but we’re going to have to educate everyone and we have to concentrate on the teenagers.”

Wilkins said, “It’s educating from the ground level. Educating elementary school kids, not about domestic violence and dating violence, but how to treat each other and good citizenship. Then middle school, high school and college, more on bystander intervention, about what is dating and domestic violence and how they can either stop it or protect themselves. This is for guys and girls. Teaching women have to protect themselves and educating good young men on being good bystanders.”

Along with educating the youth, Lelli wants to instruct educators on how to recognize the signs of child trauma and domestic abuse.

Lelli said, “I think [the solution] is everything. It’s everybody. Everybody needs to be educated. Everyone needs to know what it means to be a bystander and a good bystander and how to intervene.”

Not just as an advocate for domestic violence resolution but as an educator, Lelli understands the benefits domestic violence education can have on other professionals.

“I think it’s important to me because as a teacher, I saw what trauma could do and I saw how difficult it was for children of trauma to be able to learn in the classroom,” Lelli said.

Dr. Donald Taylor, president of Cabrini University, said, “We believe strongly that the way that we can make an impact in the issue of domestic violence, dating violence [and] childhood trauma is through education. That’s the way to really break the cycle.”

Cabrini University reaffirmed its commitment to addressing dating and family violence at its seventh annual domestic violence symposium, hosted by the university’s newly established Center on Childhood Trauma and Domestic Violence Education.

Domestic violence, in comparison to other global issues, is a relatively recent problem. While men have been mistreating and abusing their wives for centuries, this normalized social justice issue has only been recognized as punishable by law since 1994, when Congress passed the Violence Against Women Act and made domestic violence is a national crime.

Though domestic violence has been legally recognized as a crime for more than 20 years, it is still a national issue.

One in every three women is a victim on some form of physical, dating or domestic violence.

John Jordan, domestic violence education advocate, said during the symposium, “From the general standpoint, we must all recognize that for too many years, our society has looked away from family abuse and also places as much blame on the victim as it does the abuser.”

Cabrini has been committed to the combating domestic violence for about a decade now. Ten years worth of education and advocacy came to fruition with the launch of the Center on Childhood Trauma and Domestic Violence Education. Cabrini faculty

“Our hope is with the center, we can provide research, we can provide programming and provide lots of other information for the greater community about domestic violence and children of trauma,” Colleen Lelli, associate educational specialists professor and director of the center, said.

With the creation of the center, Cabrini intends to use its resources to encourage discussions of address domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault and childhood trauma as well as further work towards ending domestic violence.

“[This discussion] is just not happening in as many. Just a handful of colleges in the united states are courageous enough to take a stand and say, ‘That’s unacceptable here. We expect respect. We are looking at what a healthy relationship is,'” Barbara Jordan said. “I think, in the world, Cabrini University is a leader.”

Editor’s Note: If you or anyone you know may be the survivor of domestic abuse, dating violence or childhood trauma, seek help. On campus, Cabrini offers the Counseling and Psychological Services. Individuals can also call RAINN, the national sexual assault hotline, as well as reach out to the Delaware County Women Against Rape and Laurel House.