Cabrini students are constantly called to “do something extraordinary” with their lives and in their day-to-day actions. But what about “survive something extraordinary” or “rebuild something extraordinary?”

That doesn’t exactly describe the mission statement or curriculum but that is exactly what was asked of junior communication major Mary Jacobs.

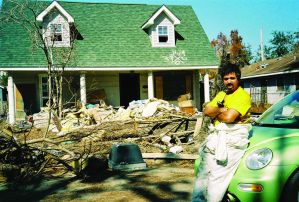

Five years ago in August of 2005, Hurricane Katrina ravaged the southern coast of our country, killing thousands, displacing entire cities and causing billions of dollars in damages. Of the affected areas, none was hit harder than Jacobs’ hometown of New Orleans, La., which saw extensive flooding when the series of levees keeping the city above water broke in the wake of Katrina’s landfall.

Having ridden out previous badJacobs recounts the approach and passing of Katrina as a relatively mundane affair.

“My family would normally stay for storms,” Jacobs said. “They are usually a false alarm anyway. For Katrina we stayed until the last day, until they made evacuation mandatory. We weren’t going to break the law, so we left.”

For the time being, Jacobs and her immediate family went to stay with her godmother in Arkansas while the storm blew over. They, much like others fleeing the coast as Katrina approached, expected a brief break from normalcy, not the arduous, uphill battle that would soon unfold.

“I packed for two or three days, not months,” Jacobs recalls. It would soon become apparent that the passage of the storm was not the end to the ordeal.

“Katrina hit, passed over, the next day was beautiful outside. Then the city started filling up with water,” Jacobs said, referring to the flooding that would slowly overtake New Orleans in the wake of the massive levee failures.

“I will always remember where I was when I heard that the levees broke,” Jacobs said. “We were in a café in Arkansas when we overheard someone saying that the levees had given way.”

The disaster had just begun.

Jacobs remembers her immediate fears upon hearing of the flooding.

“All of my family had evacuated but I had friends that I knew were still in the city that still hadn’t evacuated. I had no way of getting in touch with them,” Jacobs said. “The cell phone towers and landlines were down. I spent a week of not knowing.”

From the fateful day that the levees broke, Jacobs spent 18 months away from her home in New Orleans. Six of those months were spent living without her parents and three months were spent at a small private school where she says she didn’t fit in.

“There were so many displaced Katrina kids at that school. There was just no sympathy for us,” Jacobs said.

Even after their house was rebuilt on the same land as her former home in New Orleans, normalcy was not restored. “The local grocery store I would walk to as a kid was leveled now,” Jacobs said. “My neighborhood then was just lots around us where people hadn’t been able to move back.”

According to Jacobs, things are still not completely recovered today.

“People are still struggling with PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) and rebuilding the city. My neighbor is still in a FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) trailer.”

The biggest reminder left in her life was more personal though.

“My best friend at the time never moved back to New Orleans,” Jacobs said. “She moved to North Carolina. I only see her once a year now. That was the hardest part; you’re not supposed to lose a best friend like that.”

In spite of all she has come through, Jacobs seems to be less prone to sadness and regret than she does resentment. Jacobs feels resentment at all the mismanagement that took place before and during the disaster.

“I see how corrupt it was, engineers not preparing the city for a storm like this. I’m more angry at it now. It wasn’t a natural disaster so much as a human disaster,” Jacobs said. “I no longer have a childhood house, school, grocery store, not because of time but because of poor management.”

In addition to the unstable levee system that caused the severe flooding, there are horror stories from the supposedly failed rescue plan for those left in New Orleans.

“Everyone that could leave, left. Those that stayed did so because they couldn’t leave,” Jacobs said. “People died because they were unlucky. Maybe they just couldn’t afford a bus ticket. There were people stuck in their attics as the water rose being told by 911 operators that no one was coming for them.”

Nevertheless, Jacobs sees a bronze lining in this sea of mistakes.

“The lack of aid and preparation was so disturbing but it’s important for our history. If we forget what happened, we will repeat it,” Jacobs said.

In spite of all that has happened, Jacobs, who says she is thankful that she didn’t lose anyone in the flood, still returns home when not at school. Jacobs says Katrina has had some profound and positive impacts on her outlook.

“Being able to witness not just my experience but my whole city’s experience puts things in a bigger perspective. People put so much worth on what they have,” Jacobs said. “When you are forced to think about your attachment to the material world in such a real way, it can’t help but change you. When people lost parents and pets, what does something like a bike mean?”

Jacobs wants to make it known that she is proud of her hometown and the devastation they have risen from.

“I don’t want people to pity me or my city, I want them to learn,” Jacobs said. “I take away from this a new appreciation for the places I’m in, the people I meet and the time I get to spend with them.”