Making the decision to journey to the U.S.

Nine years ago, a woman from Guatemala made a decision that would change her life forever. It’s a journey that would force her to face challenges and dangers she never would have expected.

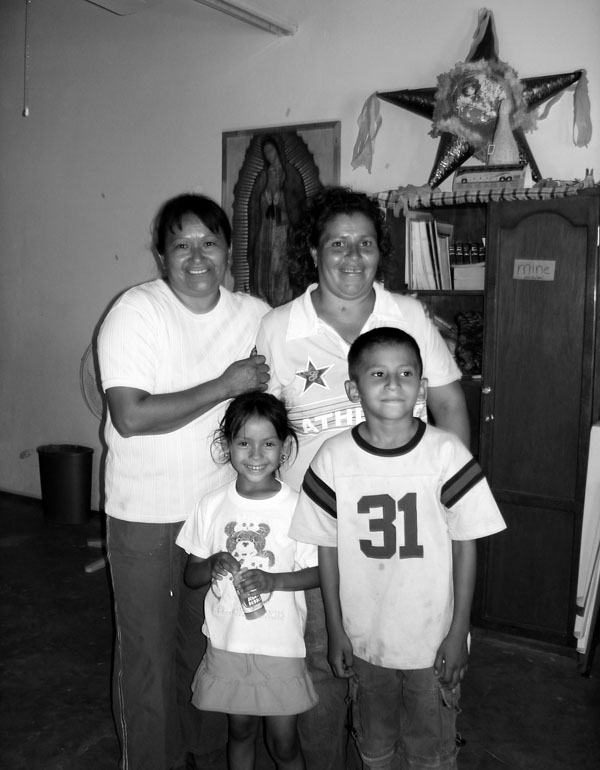

Roberta, a resident of Philadelphia, requested her real name not be used due to the recent validation of her visa. She was once a part of the more than 11 million undocumented immigrants already living in the United States.

This precarious journey northward was also one she didn’t want to make.

“I was praying we wouldn’t have to go,” Roberta said. “I didn’t want to leave my family.”

After growing up in Guatemala City as a child, she moved to the outskirts of the city after 12 years. She later married and had two children, one girl who is now 14 years old and a boy who is now 12. Just like any other average Guatemalan, Roberta led a seemingly normal life.

However a normal life to Guatemalans is in stark contrast to the normal life of an average American. According to the World Bank, about 75 percent of Guatemalans are below the poverty line with 58 percent of the population living in extreme poverty. In addition, seven out of 10 children under the age of five are malnourished.

Current economic conditions in Guatemala have worsened since the 1990s with the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement. NAFTA has benefited the large agribusiness companies of the United States, but has decimated the middle class and farmers in Central America.

Due to the economic disparity in her own country, Roberta was forced to be separated from her husband for weeks at a time. Her husband would make the long passage through Mexico to the United States to work in Texas in order to provide a living income for his family.

Over time, a family can live under the strain of separation only for so long.

“My husband wanted me to come to the United States with the kids. It was hard for him as well,” Roberta said.

Facing the challenges of migrating without documents

Roberta made the decision to put her family first and come to the United States. The first option was to come to the United States legally. But reality soon set in for Roberta.

“It’s almost impossible,” Roberta said in reference to obtaining a visa.

Current immigration laws only allow for 66,000 low-skilled labor positions for people across the globe. This leaves a gap of 434,000 in the labor force as there are 500,000 generated every year. In addition, it can take over a decade to enter the United States even if a person can get through the process.

Roberta and her children wouldn’t have to jump from boxcar to boxcar on the northward trains like many heading to the United States do. Because of her husband’s connections, she was able to secure a safe passage to Mexico. But, that came with a price. Undocumented immigrants are known to pay up to $5,000, the yearly wages of a Guatemalan, to assistant them in entering the United States.

“He [my husband] had to pay, but because he was a friend I think he didn’t have to pay as much,” Roberta said.

The ease of her journey would abruptly end. The next challenge would be to cross the Rio Grande River bordering the United States and Mexico.

“I was told ‘Someone is going to help you cross the river,’” Roberta said. “These people work doing that all the time. I said ‘How? I don’t know how to swim.’ They said, ‘You’re going to sit in here and then we’ll push.’”

With her children next to her, she crossed the river into the land of opportunity on a raft in fear of the possibility of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement turning her right back around.

Even more frightening was the possibility that these people were not friends but human traffickers. Approximately 14,500 to 17,500 people are trafficked to the United States every year for labor or prostitution according to the U.S. Department of State Trafficking in Persons Report.

Luckily, Roberta and her children would not be subjected to this fate and she made it to the shores of the United States safely.

“They had a house where we stayed for a few hours. While I was there, I was scared they could do something,” Roberta said.

Learning a new language

After what seemed like a never-ending wait, she was finally united with her mother-in-law in Texas where she stayed with her children for a short time. Yet obstacles were still being thrown at Roberta and her family.

“I didn’t speak any English. I knew how to read and write some, but it was hard to speak. It was hard to ask questions. I needed people to help me,” Roberta said.

The reality of having to pick up a second language was not new to Roberta.

“Of course, I knew that I needed to. I do love my Spanish though,” Roberta said with a laugh. “I know people who come here and they want to learn English. Even the older people still want to learn.”

Her children, having been thrown into a completely different culture, would also be faced with this obstacle. Many Americans are concerned that English would be overtaken as the primary language spoken in the United States.

Yet a report on language assimilation by the Lewis Mumford Center for Comparative Urban and Regional Research in Albany, N.Y., found that 91 percent of second-generation immigrants, like Roberta’s children, will become practically fluent in English.

“They speak English and Spanish. My daughter speaks both perfectly, but my son’s first language is English.”

Within a few weeks, another journey lay ahead for Roberta.

Adjusting to America

“A friend in Philadelphia said, ‘Come here, you can save money.’ I said okay, let’s do it. It was expensive for me. I took a Greyhound bus,” Roberta said.

Life wasn’t what she expected it would be in the United States. Her pursuit of happiness would be a struggle to obtain as she recalled the first few months in Philadelphia.

“There were four of us in one room in this house. It was awful, there was no space for us. We stayed like that for two months until my husband got the money from his job,” Roberta said.

Because she did not have a social security number due to her undocumented status she was unable to find a place of her own.

“You can’t even rent a house. Oh lord, it’s so important to have a social security number.”

Her first jobs included tasks that even teenagers searching for jobs wouldn’t subject themselves to.

“I was lucky a lot of people knew me. I had a friend and I started working cleaning houses. I didn’t know I could make a lot of money,” Roberta said.

Without the protection of the law, she was subjected to low wages.

Recalling the experiences of others she knows, she noted the long hours and small amount of pay they receive.

“People will have to work many hours in a day and they don’t make money,” Roberta said.

The adjustment to life in Philadelphia for her and her family was a constant struggle.

“Life is completely different. Everyone stays in. I don’t even know my neighbors,” Roberta said.

“There are so many drugs. I never saw people doing that in Guatemala. I walked out the door here and it’s happening.”

She soon found help in the area from the Sisters of St. Joseph Welcome Center. The sisters at the center help immigrants improve their English and make the transition into American society easier.

“It’s amazing though. They’ve helped me so much,” Roberta said. “Thank God everyone was pretty nice.”

In 2000, Roberta adjusted her status when her husband applied for a Family Based Green Card.

“I’m very happy now, I can help the way I was helped before,” Roberta said.

Cabrini SEM 300 students learn about issue firsthand

Students at Cabrini have been able to address the issue firsthand. Taught by Dr. Jerry Zurek, chairman of the communications department, the SEM 300: Working for Global Justice class immerses students into issues such as extreme poverty, human trafficking and immigration.

“Students will take knowledge and desire and use that knowledge after they graduate,” Zurek said.

Students have also been able to visit the Sisters of St. Joseph Welcome Center and the Northeast Regional Office of Catholic Relief Services.

“The class has opened my eyes to the myriad of issues that face immigrants in America. Although it seems like a cut-and-dry situation, the challenges they face once arriving here are unbelievable. I think before I thought their struggles ended once they successfully crossed the border. Now I know that isn’t the case,” Monica Burke, senior English and communication and biology major, said.

Before engaging in the class, Burke found that she was not as informed on the issue as she thought she was.

“I thought I was pretty in tune to immigration issues,” Burke said. “Now, after learning more and more, I see that most Americans have barely scratched the surface of understanding what faces an immigrant once they decide to migrate.”

Burke believes that people like Roberta also deserve the help of the community.

“It is the responsibility of a community to care for the weakest of its members. By being educated about the challenges and issues that face immigrants, Cabrini students can advocate for these members of our community,” Burke said.

Roberta also holds high hopes for the future and hopes to be a part of this community that helps out those that are making the adjustment into American society.

“This is a wonderful country where we can learn and support our families. For those that are living here undocumented, there is hope. There are wonderful people who can help,” Roberta said.